asylum process

Disclaimer: Legal Information Only – Not Legal Advice. VAAP provides resources on this website for informational purposes only. While we strive to offer helpful, relevant, and accurate information, the legal landscape is constantly evolving, and we cannot guarantee that all resources or content here remain up-to-date. The information on this website is not intended as legal advice, and should not be relied upon as a substitute for professional legal counsel. Every legal situation is unique, and individuals should consult a qualified attorney for advice specific to their case. VAAP is a small team with limited capacity, and while we do our best to connect you with valuable information, we are not responsible for the accuracy, completeness, or timeliness of the resources provided by third parties. Please verify the reliability of any external sources and updates to the law before relying on any information found here.

WHO Does VAAP serve?

VAAP serves noncitizens in Vermont. For people seeking family- and employment-based pathways, we can share information and recommend trusted private practice attorneys. For humanitarian status seekers, like asylum seekers, we can screen for relief and hopefully offer direct immigration application assistance. Most people seeking help from VAAP are asylum seekers who have experienced forced migration, circumstances that pushed them away from their homelands and pulled them to Vermont as a place of refuge. While we might think about migrants collectively as “refugees,” the reality is that relatively few noncitizens arrive with “refugee” legal status. Instead, most immigrants are under- or undocumented and must submit applications to regularize immigration status and meet immediate and long-term goals.

What are VAAP clients’ goals?

Most immediately, VAAP clients’ most immediate goals are avoiding death, bodily harm, confinement in detention, and banishment through deportation. Once immediately safe, clients’ material goals include accessing a safe place to sleep, food and medicine for themselves and their families, and the opportunity to earn income to make the first two sustainable. Long term, most VAAP clients hope to live safely with their families free from the threat of deportation from the U.S. and free from the threat of harms faced in their countries of origin, let alone free to participate safely and equitably in public and political life.

What legal options further VAAP clients’ goals?

Quoting attorney Sarah Morando Lakhani, U.S. law offers three pathways to regularized immigration status: family-based (based on “blood” relationships), employment-based (based on “sweat” relationships), and humanitarian-based (based on “tears” relationships). Programs like VAAP focus on the last, which are typically too time-intensive, politicized, and unstable for private bar coverage. Unfortunately, humanitarian pathways require applicants to excavate and display the depths of their worst experiences here or abroad without the outcome of justice being served. “Justice” isn’t an option for most but—depending on the bad things that have happened to them here or abroad—the law might offer tools to help clients meet at least some extraordinarily valid goals like immediate safety and meeting material needs.

When can VAAP clients become authorized to work?

Obtaining work authorization is usually VAAP clients’ most urgent goal. In the U.S., a work authorized social security number is the necessary precursor to working safely, opening a bank account, traveling safely between states, securing financing, and accessing public services and financial aid. Importantly, work authorization is not an independent immigration benefit one can apply for and is only available incident to some other pending “blood,” “sweat,” or “tears” pathway. Rules and processing times vary by pathways. Asylum seekers can apply for work authorization 180 days (or six months) after filing for asylum. Eligible individuals can apply for work authorization by submitting proof of eligibility and a current USCIS Form I-765.

What is asylum?

Since the mid-20th century, international and federal law have mandated that the U.S. must "withhold" removal of people who fear harm for things about themselves they cannot change or shouldn’t have to change (“protected grounds”) from which their government can’t or won’t protect them. In 1980, the Refugee Act added the option of discretionary asylum as an added benefit to withholding, offering more permanent status, family reunification, and potential U.S. citizenship. Asylum and withholding are just two of many “tears” based humanitarian immigration pathways and people are not limited to pursuing one at a time. Success depends not only on finding affordable counsel, which isn’t provided, but also on proving the “right” kind of harm to the “right” part of their marginalized identity at the “right” time and place. Even imminent death upon deportation is often insufficient.

Who is an asylum seeker?

When crossing international borders, forced migration is strictly regulated by law. When crossing inward across U.S. borders, forced migration is often wrongly labeled “illegal.” Federal law requires only that a person be present and afraid to invoke their right to a fair hearing on eligibility for asylum or withholding. There is no “wrong” way to seek asylum, and anyone present and afraid with an unexhausted claim is, by law, an asylum seeker. People cannot “be illegal” and the “a- - - -” word is harmful, even when being read out loud directly from the U.S. Code.

What are the risks and benefits of applying for asylum?

For most VAAP clients, preparing and filing asylum applications is materially emergent, but must be handled with caution and care. The sworn testimony those applications contain will follow an asylum-seeker throughout their immigration journey, lasting many years and possibly decades. Under the REAL ID Act, any inconsistent statements anywhere in the record of proceedings, however immaterial to the heart of the legal claim, can be used to find the asylum seeker “not credible” and deny their application. Denied applicants have limited appeal rights and, once exhausted, the government orders them “removed” and likely physically deports them. If the law prevents the government from granting someone asylum as a matter of discretion, the person may still be able to have their removal “withheld” but without the added benefits of permanent status, family reunification, or the ability to travel internationally.

How does one apply for asylum?

If immigration officers detain a noncitizen within 100 miles of a U.S. international border, which includes most of VT, they can apply for asylum by stating (and repeating) that they are afraid of returning to their country of origin, want to be screened for asylum, and want to speak to an attorney.

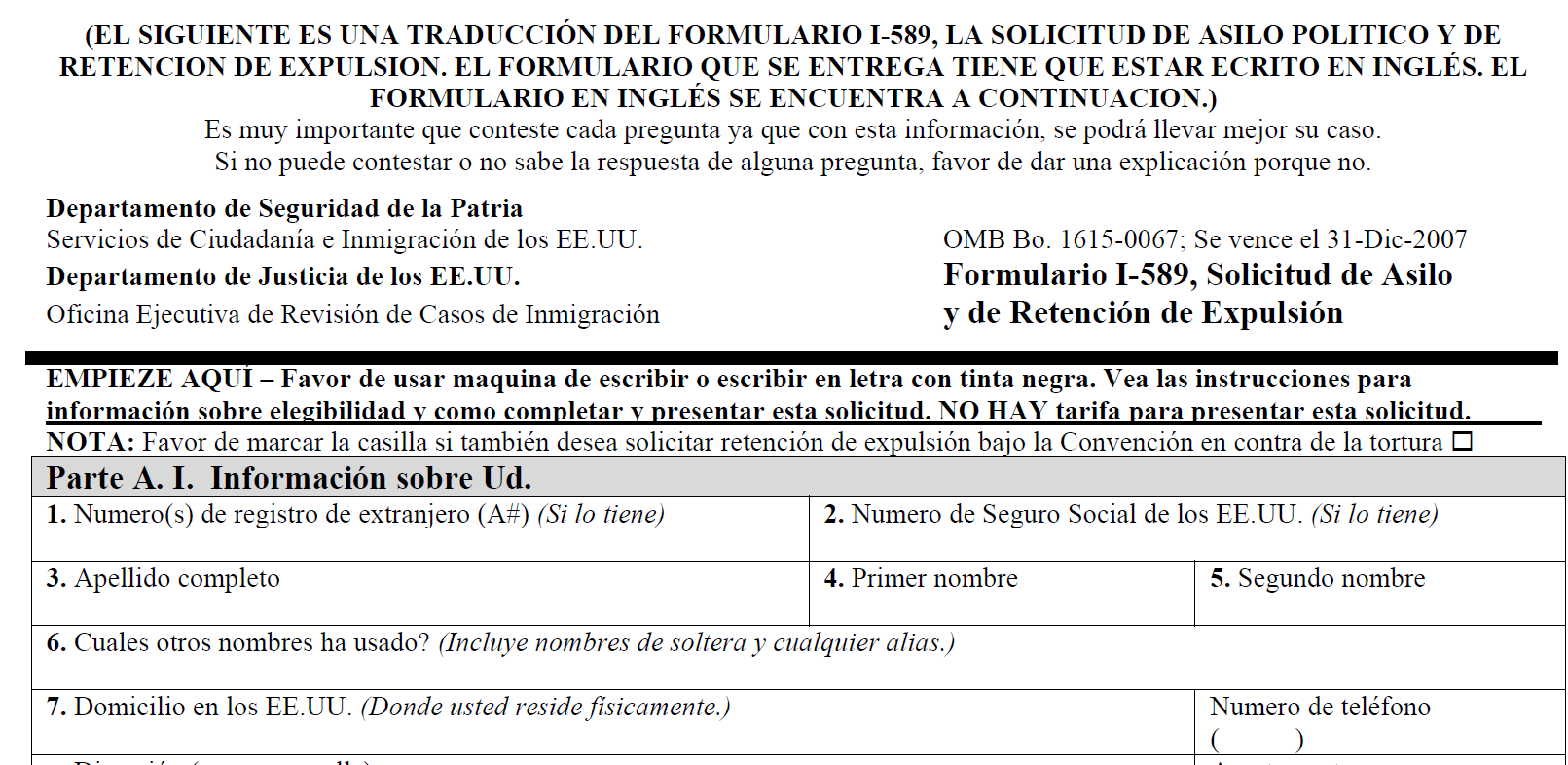

If a noncitizen is in the U.S. and not in removal proceedings before the Immigration Court, they can apply for asylum by filing a current USCIS Form I-589 with U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

If a noncitizen is in the U.S. and in Immigration Court removal proceedings, they can apply for asylum by filing a current USCIS Form I-589 with the Immigration Court.

How does one maximize their chance of winning asylum?

Without access to legal counsel, an asylum seeker is exponentially less likely to be granted asylum and instead be deported, often into life-threatening situations. Even with representation, the Executive Office for Immigration Review reports an asylum grant rate of only 41% as of 2024, a figure likely to worsen into the next administration. Under these unfavorable circumstances, VAAP aims to give Vermont noncitizens more just and open access to the U.S. immigration legal system so they can fully participate in our community and have a life of dignity—or at least meet their immediate safety and material needs along the way.

Access our virtual resource library here, request our legal help here, offer to volunteer here, learn about our non-legal partners here, attend our events here, follow our work here and subscribe to our newsletter here.

What should I expect from an initial meeting with an attorney, and how should I prepare?

One important thing to understand before meeting with your attorney is the different kinds of asylum, and what choices you might want to pursue with your attorney. This resource gives an overview of the different types of asylum, and how to know what kind you are seeking.

During your first meeting, the purpose of the meeting in general is for your attorney to gauge your case, hear your story, and provide feedback on what they can do, as your legal representation, to help you. Coming in with questions for them is a great idea, as it is their job to answer anything you might be confused about. Here is a great list of questions that are important to ask and understand the answers to.

Before you meet with an attorney, you have to have certain papers filled out, and brought with you to the meeting. You should bring your passport, your I-94, any documents you have received from the government, anything related to prior immigration cases, any criminal records, and any evidence related to or important in your current case. For a more comprehensive explanation, look here.

Finally, if you do not speak English, you will hopefully be provided an interpreter, so it is a good idea to understand some legal terms. For a list of legal terms explained simply in plain English, click here! If Spanish is your first language, here is a list of translations that will help you communicate.